The Wake of “the Bricklayer” and his Story of Life

By John Kass

Have you heard all the political screaming lately? Who could miss it?

In Washington the Democrats were busy burning Republican witches, their media choir chanting through billowing incense to protect any inquisitors who got too close to the flames, while the Republicans gathered their wood and set their stakes, planning on burning their Democratic witches in November.

And in Chicago, the mayor and the teachers’ union were busy burning each other down too, even as they torched the futures of the city’s most vulnerable schoolchildren.

It was all political smoke, political fire and political screams. But there was refuge, and we found it.

We found it in a quiet place where people came to remember a good man who made his mark in the world:

It was the wake of “The Bricklayer.”

He was 87 years old when he died recently. In his coffin, those those large hands of his were folded in front of him, with a rosary. He was at rest.

He wasn’t really a bricklayer. Betty just called him that on account of his big hands. She was terrified by them at first. When she met him, all she’d say was, “My God, those hands!”

Later, when she gave birth to our twin sons, those big strong hands would save her life, and the lives of our boys.

Unlike the politicians who scream and dance in the smoke of the fires they set, the bricklayer was not a man of destruction and noise. He was all about life, and faith and family.

His name was Dr. Ronald Lorenzini.

He was a physician who brought more than 7,000 babies into the world. At the end, if the angels asked him “What did you do with your life? Did you leave your mark for good or ill?”

He could tell them: “I helped more than 7,000 babies to be born. I valued life.”

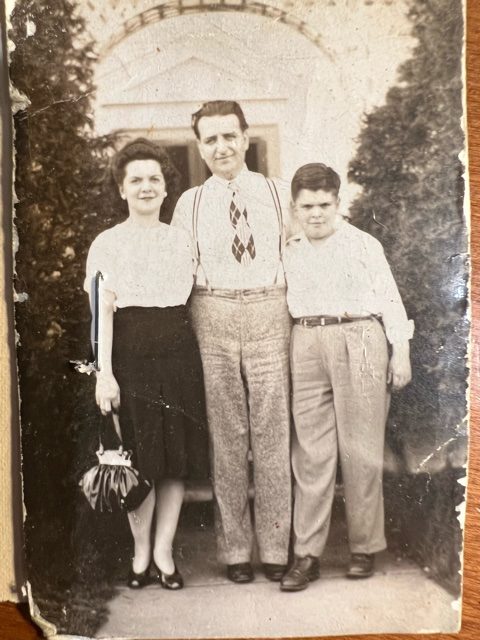

You can see him in the photo at the top of this column, as a boy pictured with his parents And you see him here as an old man, toward the end, with his wife and children at a recent family event.

Think on all the things you could do with the life you were given. Perhaps wealth, adventure, glory with the multitudes shouting your name? Now think of another life, a life that would bring 7,000 babies, 7,000 more lives into the world. A life that valued and protected other lives. Think on that for a second, of what it means.

“He was such a force, with a great big bark, but so gentle on the inside,” said his daughter, Dr. Nancy Lorenzini, an anesthesiologist now of Cedar Rapids.

She followed her father, her mentor, into medicine, working in his office when she was a teenager.

“I remember once he threw a patient into the back of the station wagon,” she told me. “The baby was being born and the cord had wrapped around the neck, and he raced to the hospital with me sitting next to the patient, my hand keeping the baby back.

“I was just 16. My sister answered the phones. I was the one helping patients to the examining rooms. We both got to see a different side of our father, different than just ‘dad at home.’ And because of that, I became a doctor.

“He was of a generation of physicians that’s lost now,” Nancy Lorenzini said. “My husband, a cardiologist, is like this, but then, he spent time with my dad.”

Ron Lorenzini was born in Cicero, Illinois, the only child of Italian immigrants Nello and Adele. They were tavern keepers. The family lived in an apartment above the tavern. And up and down the block in homes and apartments in the early 1930s and 1940s, they had their village. Aunts, uncles, cousins, second cousins, and so on, generations of people of the same blood. A large Italian tribe.

Nello Lorenzini wanted a different life for his only son. He’d talk to him about becoming a doctor. And when Ron Lorenzini enrolled at the University of Notre Dame, he took a few pre-med courses and knew what he wanted to do for the rest of his life.

He wanted to heal people. And bring babies into the world.

As a young doctor he worked at Cook County Hospital which was well known for its high level of care for newborns and their mothers. And later, he built a practice in the Western Suburbs of Chicago.

Some of you who are loyal readers and have been with me for years may remember that my wife and I knew Dr. Lorenzini.

We had twins coming. We were overwhelmed. Our first doctor who was recommended to us examined Betty, took several tests that we were told were necessary. And this first doctor said that according to the tests, the babies were healthy and fine.

But there was something else.

Because we were soon-to-be parents of “multiples,” he told us that, if for any reason we wished, he could “help” us in another “procedure.”

This other doctor called the procedure by a passive name. “Selective reduction,” he called it. If you say those two words in a soft voice, they sound heavy with neutrality. They are clinical and scientific. But the meaning is about supremely violent murderous force.

My wife’s eyes narrowed as she looked at him as he spoke of “selective reduction.”

“You’re talking about an abortion,” said Betty, standing up. Turning to me, she said, “Let’s go. We’re going to find another doctor.” She didn’t say another word to him.

We found Dr. Lorenzini. A friend at work, Laura Moran recommended him. We brought the test results from that other doctor, the one of violent euphemism, to Dr. Lorenzini’s office.

There was a simple card in his waiting room for all to see. The card said that this medical practice would not perform abortions under any circumstances.

“Good,” Betty said, smiling. She said she felt better after reading the card. So did I.

Dr. Lorenzini had Betty’s file, including the test results from that other doctor we’d left behind. He asked if we wanted boys or girls or one of each.

“We don’t know,” Betty said. “We don’t want to know. We want it to be a surprise.”

He looked at me. I shook my head and shrugged. I wanted to know. But I was just going along, because well, it was beyond my control.

Without expression, he folded the file and put on top of his desk. He said was going to take Betty into another room and examine her there.

He gave me a blank look. There was no wink behind it. Nothing. He just patted the file on his desk. And then he took her into the examining room. With the file on his desk, as soon as they left, I opened it and quickly found what I was looking for, the phrase “chromosomes consistent with…”

Yes, it was wrong of me. I shouldn’t have done it. It was a sin. But I wanted boys, and so, I peeked.

But from from that moment, I’ve loved the color blue. I thought we might have a daughter, later, who I could spoil, a girl to bring me a glass of water when I got old. Some girls dote on their daddies. Boys want the keys to the car.

And Dr. Lorenzini? If he suspected, he never said. I finally told Betty about it, years later.

Hers was a difficult birth. Difficult is not the word for it. One of the boys was breach. I was there in the delivery room—because husbands were expected to be in that room, helpless, to give support. That’s when Betty really started screaming.

“This woman has not been properly anesthetized!” he said.

I sat in the husband’s place at the end of the table, with the anesthesiologist, as my wife screamed. I stared at that anesthesiologist. I couldn’t tell you now what he looked like, I was focusing on just a piece of him:

On the corner of his eye where it met the nose. What was I thinking? How I’d just stick my fingers in the eye and find purchase to tear that head apart.

Terrible thoughts, yes. Horrible thoughts. But I thought them. Still, I made no aggressive move. I was quiet, sitting there, staring at the corner of the anesthesiologist’s eye as Betty screamed and screamed.

Dr. Lorenzini started shouting:

“Get the father out! GET THE FATHER OUT! GET THE FATHER OUT!” Dr. Lorenzini said.

The nurses got me out. They hustled me so fast I was backpedaling through the doors. Then he went in with those big hands and did what he had to do. He didn’t hesitate. There wasn’t time. He got the one boy, then the other. They were fine.

But Betty wasn’t. She wouldn’t stop bleeding. She was going to die. It many hours, and a whole team, but he finally stopped her hemorrhaging.

He saved the boys and he saved her.

Weeks later, I was driving a lawyer to a TV news taping. He said we could make a lot of money in a lawsuit. I thought about pressing his seat belt button, then pushing him out the door to bounce on the Kennedy Expressway.

But I didn’t. Still, I never spoke to the man again.

At the funeral home the other night, with all his grandchildren standing, there were many former patients paying their respects. My wife was one of them.

“He saved my life,” Betty said. “He saved the lives of our sons.”

We wept together at his coffin. I didn’t want to get emotional but it happened. We remembered those days and nights and how he saved our sons, how he worked for hour after hour to stop the bleeding and save my wife. We patted those big hands. Said goodbye through our tears and made the sign of the cross.

Unlike the politicians, Ron Lorenzini lived his life for the good.

He grew up above that tavern in Cicero and delivered thousands and thousands of babies.

In the old days, when doctors could do such things, he’d comfort frightened young girls who were considering abortions. He’d find good families for their babies, families he knew, so the child would have a life, so the young mother wouldn’t suffer the horrible guilt of killing her baby.

I don’t know everything about him. He was a man, and all men are imperfect. But he brought more than 7,000 lives into this world. He so valued life. He saved our sons and my wife. I could never thank him enough. But there, as he rested, I offered what I could; a husband’s thanks, a father’s thanks.

Without him, our family would have been broken. But he did what had to be done. He gave our family a chance.

That’s all you can ask for. A chance.

Thank you Dr. Lorenzini.

God bless you, Bricklayer.

-30-

(Copyright 2022 John Kass)

If you want to get access to all of my columns, subscribe here.