When Hollywood Calls, Know When To Quit

by Cory Franklin

August 11, 2023

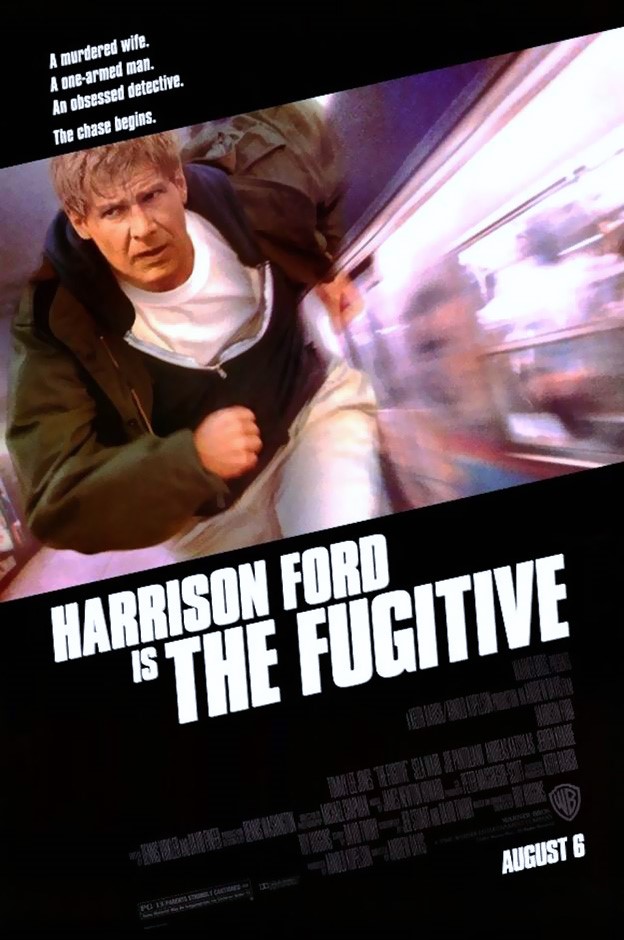

This month marks the 30th anniversary of the filming of The Fugitive in Chicago. Through an unusual turn of events, I was asked to be a technical adviser to Harrison Ford in some of hi medical scenes and also to make are the medical sets were realistic. It was a great job and a great movie. Here is one of my stories, excerpted and edited from my book Cook County ICU about working on the movie.

One of my jobs as technical advisor was to make sure the medical set was as realistic as possible. Some filming was done on a refurbished three-story school building on the South Side. One floor was made to look like a prison (the one Richard Kimble is sent to), another floor was made to resemble a prosthetics lab, and one floor was supposed to be a hospital emergency area. That was my responsibility.

One day, some of the assistants brought me to that part of the building which was being reconfigured to look like the hospital. There were extras wandering around in costume, people dressed as doctors, nurses, security guards, janitors, etc. My charge was to recommend physical details that would make the whole thing look realistic.

I have to admit it was fun walking around giving suggestions to make a movie set look like a hospital ward. And my word carried weight. For instance, I was asked what books might be found at the “nurses’ station”. When I replied a nursing handbook and a Physicians’ Desk Reference, some assistant snapped his finger and some lower-level assistant was sent out to procure them. A couple of hours later, there those books were on the “ward”.

When I was done furnishing the “emergency room”, it looked pretty good. Between all the medical details and the realistic looking cast, you might be excused for believing you really were in a hospital. Then I learned my lesson about Hollywood. Hollywood wants reality, just not too much of it

The next day I came to the set to watch the shooting. It was a simple scene, a bunch of extras dressed as hospital personnel and patients walking down the hallway. They told me I did a good job, it looked like a hospital. I felt really proud. As they did the shoot, I felt like I owned a piece of the movie.

Until.

About the third take, as the extras walked down the hospital hall, a man suddenly came rollerblading down the hall. He was supposed to be an orderly. While he was only on camera for about five seconds, the incongruity of someone rollerblading in the hospital became the focus of attention- and, in my mind, destroyed the verisimilitude of the scene.

About the third take, as the extras walked down the hospital hall, a man suddenly came rollerblading down the hall. He was supposed to be an orderly. While he was only on camera for about five seconds, the incongruity of someone rollerblading in the hospital became the focus of attention- and, in my mind, destroyed the verisimilitude of the scene.

At that point, I was feeling pretty confident, maybe even cocky. I mean, after all, I just helped put all this together. So at that point, I went to the person in charge of the scene and said,

“You know, that would never happen in a real hospital. Nobody rollerblades down the hall.”

The assistant director, or whoever he was, gave me a cold stare. At that moment, all my past contributions to the movie didn’t mean anything. He immediately let me know where I really stood in the hierarchy. “When we want your opinion, we will ask for it. Got that?”

The rollerblading orderly stayed in the movie, and I very nearly didn’t. Because Hollywood wants reality, just not too much of it.

I heard that one more time.

Harrison Ford and I were working together on a scene where he was “playing me”. The plot point was that he was undercover in the hospital as a janitor when they brought a young boy to the emergency room with chest trauma. He was supposed to have a life-threatening condition, a tension pneumothorax, which would be immediately evident on his chest x-ray. Once diagnosed, the little boy would have to go to surgery.

As Richard Kimble, the janitor who was really a doctor, watched the situation, he saw the doctor who was caring for the patient leave him without looking at the x-ray. Julianne Moore, the head doctor, told “janitor” Kimble to move the patient to an examining room. Instead he looked at the x-ray and diverted the patient to the surgery that would save the little boy’s life.

While we discussed the scene, Ford asked me what I would do in that situation. How would I act as I wheeled the boy in the elevator to the operating room. What would I say?

“The first thing you have to remember is that the little boy will be afraid. He is in a strange situation, having trouble breathing, severe chest pain, he is really scared. What you want to do is allay his fear. Reassure him. He wants to know where his mother is. Tell him she’s coming. And then talk to him about something else he’s interested in, that takes his mind off the current situation. Ask him if he plays sports. Baseball, football, whatever. Reassure him everything will be OK.”

Harrison Ford did that elevator ride with the kid about as well as anyone could do it. Olivier, Brando, DeNiro – nobody could have reassured that kid better than he did. He was so good, I thought they should use that segment of him to teach doctors how to talk to kids. He could be a technical advisor to doctors.

I watched the scene that day with Andy Davis and we were both ecstatic about how it came off. So much so, that he decided to watch it again.

And then I saw the mistake – the perfect is the enemy of the good.

The second time, I noticed one of those movie gaffes every movie has. As Ford is wheeling the young boy into the elevator, he looks at the x-ray.

And he is looking at it backwards.

This is not really a big deal; the shot lasts for less than five seconds. But when your job is technical accuracy, you are supposed to notice things like that. So I had to say something. Of course, it didn’t occur to me that reshooting the whole scene just for that might be a big deal. And there is no guarantee it would come off as smoothly as the first time. So I said,

“Andy, watch right there. Kimble is looking at the x-ray backward. The heart is on the right, it’s supposed to be on the left. Any doctor would flip it around to look at it.”

In the time it took me to say that, the whole shot was over.

He looked at me sternly and said,

“When we want your opinion, we will ask for it. Got that?” The shot stayed and from then on, it was speak only when spoken to.

-30-

About the author:

Dr. Cory Franklin

Cory Franklin, physician and writer is a frequent contributor to johnkassnews.com.

He was director of medical intensive care at Cook County Hospital in Chicago for more than 25 years. An editorial board contributor to the Chicago Tribune op-ed page, he writes freelance medical and non-medical articles. His work has also appeared in the New York Times, Jerusalem Post, Chicago Sun-Times, New York Post, Guardian, Washington Post and has been excerpted in the New York Review of Books. Cory was also Harrison Ford’s technical adviser and one of the role models for the character Ford played in the 1993 movie, “The Fugitive.” His YouTube podcast “Rememberingthepassed” has received 900,000 hits to date. He published “Chicago Flashbulbs” in 2013, “Cook County ICU: 30 Years of Unforgettable Patients and Odd Cases” in 2015, and most recently coauthored, A Guide to Writing College Admission Essays: Practical Advice for Students and Parents in 2021.

Comments 14

Dr Franklin — thanks for the column. The devil is in the details, especially where health care is concerned. A number of years ago a documentary for the Discovery Channel was produced about the Federal Disaster Mortuary Operations Response Team and an actor portraying a forensic dentist is reading the bitewing x-rays upside down! No idea who was tech advising for that scene. Also in the original CSI, procedures for collecting evidence in a Bitemark case were reviewed prior to the episode being shot by a Board Certified Forensic Odontologist (Dentist. ) Writer was told “that’s not how it’s done.” Needless to say, 4-5 weeks later when the episode aired there was the wrong procedure. Correct one clashed with the desired story line!!

Thanks too for your time at the best ER in the country really saving lives.

Gee, Doc, you could have been dealing with a high school administrator. Them folks want no back-sass from them what knows. No how.

John, in the “about the author” section, could you correct the second paragraph or fill in the missing words. Thank you. Very interesting story.

Loved that movie!! Thanks for the great background story!! Now I need to watch it again!!

Years ago I was present in a local ER for a test Trauma, i.e., we did not know if the Trauma

was fact or fiction. Paramedics and police brought in multiple car accident victims.

One young woman supposedly unconscious was placed in a trauma room with Doctors, Nurses, Techs and equipment ready to go.

A Nurse had a scissors to cut the patient’s blue jeans off when the “patient” suddenly sat up

and proclaimed “Don’t cut my jeans off, I just bought them yesterday. I’m Ok I’m just acting.”

Everyone stopped and was taken aback, Test Trauma over.

The Hollywood people he dealt with were rude and really lacked manners. How dare you suggest improvements to their artistic ‘masterpiece’.

I really enjoyed Cory Franklin’s column today about the Hollywood insider stuff on one of my favorite actors and movies. John, you are lucky to have this man as a friend and co-writer!

Matt Marciniec

Oh, how many times I would have loved to tell Hollywood libs “When we want your opinion, we will ask for it. Got that?”

What a great story about opportunities and limits!

First dvd I ever bought after buying a 5-speaker surround sound system from United Audio.

The train crash made it all worth it.

Great story. Got the point. But since we’re talking about medical details, a kid with a tension pneumothorax needs a stat chest tube inserted in the ER (not a big deal really – but a delay is) … not the OR … certainly not at that moment … and certainly not wheeling a kid up to OR in the elevator. That is just plain wrong. Of course that would change the whole narrative and I am sure be dismissed out of hand anyway. The “back ward” Chest X-ray? Maybe the kid had situs inversus.

Hold please. Need to look up “verisimilitude”…..

noun

the appearance of being true or real.

…ok, I’m back. Great column!

“Need to look up “verisimilitude”…..

noun

the appearance of being true or real.

…ok, I’m back. Great column!”

Perfect!

John, I’ve been a subscriber from the start, thank you. I also check CWB daily and I’m upset just like everyone else. More so with the BS sentences handed out to convicts on plead down charges. I’m sure you’ve noticed this as well. Where is the justice for the victims? Those convicted are out after half of their sentence. I can’t believe what Kim Fox’s staff does and 5he Judges agree to. The judges have 5he power to override those recommended charges. How about a column on this egregious miscarriage of justice.