The Church of Baseball

By John Kass

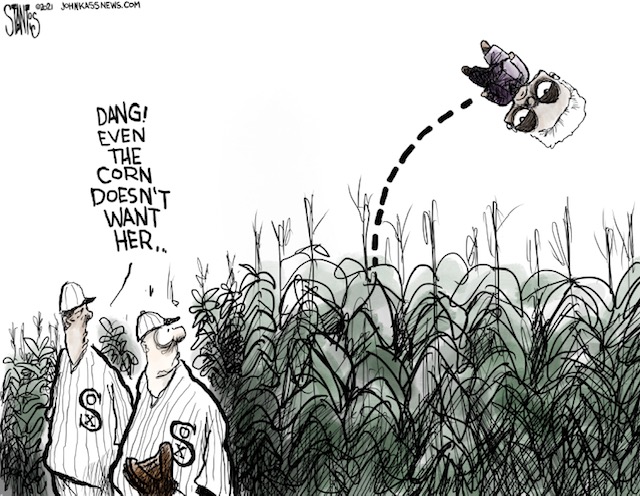

As you can plainly see at the top of this column about The Church of Baseball–and that magical “Field of Dreams” game in the Iowa cornfields between the Chicago White Sox and the Damn Yankees—everything leads off with a brilliant Scott Stantis cartoon.

It depicts Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot cast out of heaven, or at least the heavenly Iowa corn.

Don’t be sad for Lightfoot. She has been quite cruel, to her city, to her demoralized police force and their families, and just about everyone else who dares question her reign. But then, baseball can be cruel, too. The baseball gods are often cruel, as every fan knows.

Besides, it just can’t be helped. Stantis is my friend. We worked together for years at “the paper.” He’s still publishing editorial cartoons there and drawing his daily his “Prickly City” comic strip and podcasting. You can follow him at @ScottStantis. He graciously sent this cartoon to me and so, I’m using it.

“Isn’t the corn a metaphor for heaven?” Stantis said. “Or is it an allegory? Either way, the corn is heaven in “Field of Dreams” and in this one, she’s been kicked out of heaven.”

As a loyal subscriber he read my column advising Lightfoot to make a pilgrimage to Iowa for that “Field of Dreams” game and then disappear. I hoped she’d put on a tiny Sox bat boy throwback uniform and, though very much alive, vanish into the corn like the ghost ballplayers in the movie.

Stantis must have been struck by the part where I whined like a baby over not having one of his Stantis cartoons.

“I’m in the car on the way to the beach,” he texted while drawing, a testament to his Homeric talents. “I’ll send it to you in a few and you can put it up on your site.”

As you can see, it depicts the beleaguered mayor of Chicago cast out of the corn, flung so high upside down that if she’d been a gymnast, she’d have suffered the terrible “twisties.”

“Dang!” says a Sox player in a throwback uniform as Lori flies out of the corn. “Even the corn doesn’t want her.”

So, on that magical baseball night, Stantis led off with his killer cartoon. And White Sox shortstop Tim Anderson, the heart of the ballclub, ended it all in Hollywood fashion, with a two-run walk off homer to win the game 9-8.

Sox win! Sox win!

“Iowa is heaven!” said my buddy, loyal Sox season ticket holder Thom Serafin who magically scored two tickets and took his wife Ann. “It’s heaven. I mean it. Iowa is heaven. Can you hear me?”

Yes, I can hear you. Heaven has a decent cell connection.

That game, amid the myth-inspiring and ripening corn of August, was a time machine. It was welded together with nostalgia, and fueled by the ingenious marketers of the multi-billion-dollar enterprise called Major League Baseball.

MLB executives used The Church of Baseball to wash away their sins without having to confess anything. They stripped Atlanta of the All-Star Game and caved like cowards before the poisonous political race hustling of Stacey Abrams and President Joe Biden.

But they didn’t talk about that on the broadcast.

The appeal to America’s baseball soul flows from the pages of W.P. Kinsella’s fine novel, “Shoeless Joe” upon which the epic movie “Field of Dreams” was based.

It is a liturgy. And the hymns of that liturgy call out to what we long for, what we desperately want to remember, a game of catch with your dad, your mom, your children, a favorite uncle, brothers, a sister, your friends.

During the game broadcast, play-by-play announcer Joe Buck and “Field of Dreams” movie star Kevin Costner talked about baseball, about those special games of catch, and crying. Yes, there is crying in baseball, especially that last scene in the movie, which is the most guy-cry scene in Hollywood history.

Perhaps “guy-cry” is also an anachronism. These days, we are all encouraged to weep publicly. Stoics are viewed with suspicion, as subversives.

So where does Lightfoot fit in? Well, she’s a Sox fan, and a former athlete.

Former President Barack Obama–whose political clique is now itching to control the mayor’s office in Chicago—portrayed himself as a “lifelong Sox fan.”

Yet when asked on a national baseball broadcast to name his favorite White Sox players, “lifelong Sox fan” Obama couldn’t name one. Not even Dick Allen. And he referred to the old ballpark as “Kaminsky Field,” not Comiskey Park. But that won’t deter the Obama Machine from pushing Chicago into building a multi-million-dollar public temple of love and adoration in his name, on priceless lakefront park land, as if he were a god.

There won’t be any temples for Lightfoot and she knows it. But she does like sports. She played basketball, volleyball, and softball in high school. And I’d bet she could name her favorite ballplayers from Cleveland.

But in her other, rather bleak life, as mayor of Chicago, there’s no magic around Lori now. Cast out from the corn, stuck in the grim present, in a hell of her own making, she’s locked the gates behind her just like Pete Rose.

Even if she had listened to me for once and vanished into the corn as I’d asked, wouldn’t she eventually have to come out?

If I were out there alone on a magical Iowa summer evening, and the mayor of Chicago—in a little Sox bat boy throwback uniform–emerged from the cornstalks, with those angry Lori eyes, short legs churning, sprinting toward me, you know what I’d do?

I’d scream and probably faint. I might only get a half scream out, like “Heep!” before collapsing into a puddle of spineless goo in the magical outfield.

My friend Jimmy Banakis offered an alternative scene:

“How about Lori disappearing into the cornfields, and the ghosts of Richard J. Daley and Bill Veeck emerging with bagpipes?”

I’d be dumbstruck, at a loss for words. Richard J. Daley, the real Mayor Daley, loved the city and loved the Sox. He grew up at old Comiskey, with his mother insisting that all her children and grandchildren never leave a Sox game until the game was over.

And Veeck, who lost his leg in the U.S. Army and owned the ballclub twice, was the thumping heart of baseball.

So, I’d ask them to tell me Luis Aparicio stories about the great Venezuelan shortstop. I never met Aparicio, but when I was a little boy, I’d talk to Little Looey almost every day when we lived at 52d and Peoria.

He’d show up on the sidewalk, in his uniform, like those ghost ballplayers in the movie, when my mom would send me to Leo’s corner grocery.

Leo had fantastic candy, like those sugar dots on paper, and he had a long wooden pole with tongs at the end to pull down a can of corn from the high shelves. He’d catch the can as it fell, like an easy pop-up fly.

Hence, the “can of corn” that Hall of Fame broadcaster Hawk Harrelson referenced in Sox broadcasts. Every time the Hawk would mention it, I’d think about walking to and from Leo’s store with the great Aparicio, his spikes clicking on the sidewalk.

The Aparicio apparition and I would talk about the Sox, about life, about the dreams I had the night before, but mostly about the odd customs of these strange people called Americans. As a boy in an immigrant family, I cleaved to baseball and rejected the sport of my father, soccer. I was determined to find my place in this country, and prove my worth in the American game and so become truly American.

Because I was a voracious reader as a boy–a certified bookworm who couldn’t hit then and was always stuck into the humiliation of right field in our pickup games–I studied the catechism. I studied it desperately, like some convert at the monastery who’d been recruited from some barbaric horse tribe. And I began to love it.

The novels of John R. Tunis, including “The Kid From Tomkinsville” series about small-town pitcher Roy Tucker’s rookie season with the Brooklyn Dodgers, and all the short stories and hagiographic baseball biographies I could find. Later as a young man, came the novels of Mark Harris, where you could hear echoes of Tunis archetypes; and much later, Bernard Malamud’s “The Natural.”

I read it once at sea, missing America so much that it was painful. Malamud’s great novel had little to do with the Church of Baseball–it was quite heretical–but Hollywood recast it into a Church of Baseball pillar, with Robert Redford as as the fair knight of virtue. And “Bull Durham,” another Costner vehicle, was also inserted into the church to shore up its sagging dome.

But with the juicing scandals, and sports media having an inkling about the juice–while ignoring it in its early stages, cheerleading the juicers as it metastasized—my old faith in the church curdled. I left and locked the door behind me. Perhaps that’s called “growing up.”

Fly fishing is sport for me now. The fish don’t juice. And the only juice for fishermen is a good scotch by the fire. And hunting, if I ever get this knee fixed.

And watching prizefighting, because, like Chicago politics there is an honesty about its corruption, they don’t steal your soul, just your money. Most fighters don’t grow up having their asses kissed, most grew up never thinking they were entitled or special.

And the Beautiful Game, though I don’t look for virtue there, but am drawn to the speed and pace and the magnificent, flowing geometry of the game.

But some of us still recognize the nation’s need of the Church of Baseball, as a once-common culture shakes in violent, and endless spasm.

Now, our fiction desperately seeks out old places and old ways as if they were safe spaces.

It’s as if we are the forgotten Sarpeidonians, from a doomed planet in an old Star Trek episode, with Sarpeidon about to be wiped out in a supernova, and the inhabitants desperately file into their time machine called the Atavachron, to be whisked back into some relatively safe and ancient past of theirs.

Other iconic archetypes of American fiction are forgotten– the cowboy, the pioneer, the lone detective like a knight errant. These once exemplified what we called American virtues: self-reliance, individuality, courage to stand alone against a frantic mob, and are now frowned upon by the priests of culture and are discouraged.

Instead, our comforting fantasies now are pulled from the early middle-ages, where the virtuous speak in bluff Scottish accents.

Our fictional action heroes are bureaucrats with guns and high-tech communication devices. Hollywood offers an endless menu of caped, costumed super-heroes from the comic books of our youth, presented as gods and demi-gods.

Even though we know that the Church of Baseball on display the other night is now dominated by cynical manipulators, we still filed in to hear Joe Buck and Kevin Costner sing the hymns. We look to the past, yearning for structure, for permanence, for the childlike embrace of comfortable myth.

In an old essay on “Field of Dreams,” Kevin Hagopian of Penn State University explained it this way:

“This is a film that knows that baseball is a place in a boy’s memory where the rules are clear, where the soda pop is always ice-cold, and where there’s always the chance of an autograph from Mickey Mantle. Most of all, it’s a man’s world, where the men seem just like gods.”

Where the pop is always cold, and the gods come from the corn.

And so, if you were in Iowa, and saw an angry-eyed Lightfoot, freshly cast from the heavenly corn, and also the chuckling ghosts of the real Mayor Daley and Bill Veeck emerging from the cornfields, walking toward you, what would you say to them?

There’d be only one thing to say to them.

Guys, wanna game of catch?

-30-

(Copyright 2021 John Kass)

Comments 1

Just surfing through the older columns for fun I came across this one and had to ask. Wasn’t Bill Veek a marine?