Lent’s Bright Sorrow

By Father Paul Siewers

March 24, 2024

Lent comes late for Orthodox Christians this year. Forgive us.

It starts on the night when many Americans are celebrating their secular version of St. Patrick’s Day with green beer and in Chicago green river.

It will end after 40 days on this “old calendar” in the week of Pascha, or Orthodox Easter, which this year falls on May 5, when most Americans will be celebrating Cinco de Mayo.

Orthodox Lent arrives in a different spirit as well as in its own time zone.

Instead of the Catholic Ash Wednesday’s display of the penitent burned Cross on the forehead, Orthodox Lent starts with Forgiveness Vespers on the eve of its first day.

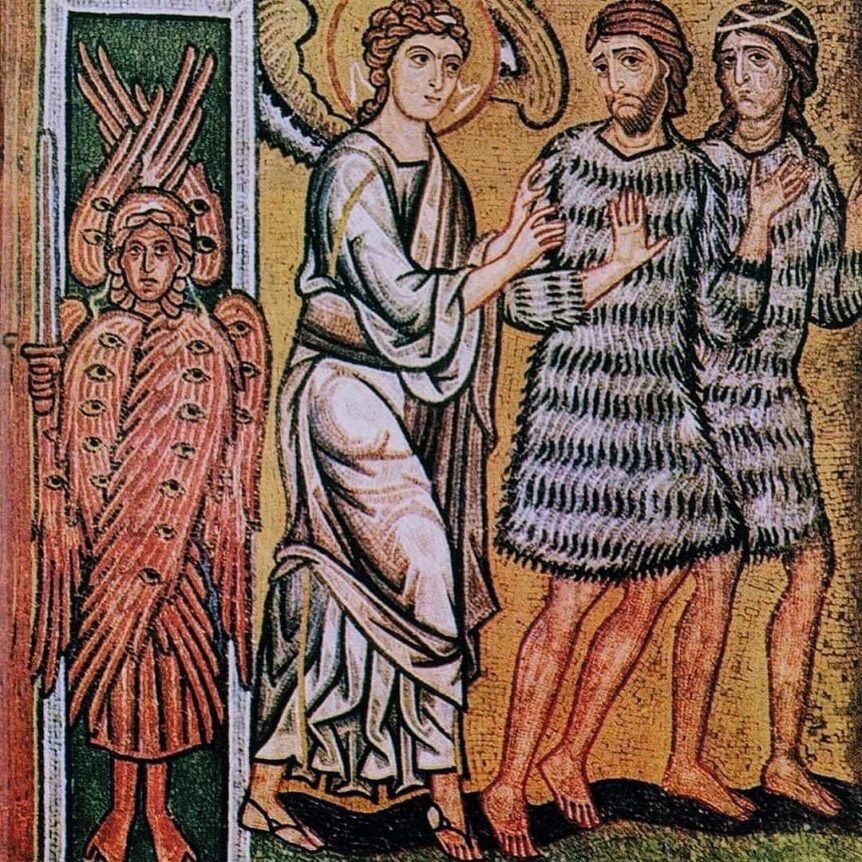

That’s what Adam and Eve never did, ask forgiveness in the Garden.

Giving forgiveness while seeking it becomes the first step of repentance in preparation for experiencing again the cosmic drama of the Crucifixion and Resurrection, to regain Paradise.

As the rubric for the service states:

The priest gives a word of instruction appropriate to the occasion and then stands beside the analogion, and the faithful come up one by one and venerate the icon, after which each makes a prostration before the priest, saying, ‘Forgive me, a sinner.’ The priest also makes a prostration before each ‘May God forgive. Forgive me, a sinner.’ The person responds, ‘May God forgive.’ and receives a blessing from the priest. Meanwhile the choir sings quietly the Irmoi of the Paschal Canon, or else the Paschal Aposticha. After receiving the priest’s blessing, the faithful also ask forgiveness of each other.

One of the Paschal hymn verses mentioned offers a reminder of what is to come, and the sorrow along the way: “He who of old freed the young men from the furnace, becoming human suffers as a mortal, and through suffering He clothes the mortal with the glory of incorruption…”

Lenten experience also includes fasting from meat and dairy and fish, and wine or hard liquor, and traditionally foregoing other sensual pleasures as well. It aims to instill a sense that it is in losing our life in Christ that we mystically find ourselves, not by asserting ourselves. The late Dartmouth professor Donald Sheehan said that was the great lesson of the writings of the most famous Orthodox Christian modern writer. Fyodor Dostoevsky in his novels emphasizes how, in the words of one of his characters, “we are all partly responsible for the sins of each other.” We shouldn’t lie to each other or to ourselves about how great we are, but should seek forgiveness from God and each other and give it freely.

Dostoevsky’s fictional courtroom dramas illustrate how cut-and-dried legalism never fully plumbs the human heart. By omission or commission, we’re all at least a little guilty to one another, and often more than a little. It’s like the old cliché about the butterfly flapping its wings in South America, and how that can cause a hurricane in Africa. What we didn’t do from lack of deep compassion and courage may contribute to great evil across many complex interactions and alternative futures.

Slavs call such mystical unity among people under God sobornost. Greeks have the term koinonia for such mystical communion. The American founders, however unorthodox, tried to describe this in their own way as being created equal, all “endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights.”

Whatever the wording, it all suggests we owe each other some forgiveness and much humility, rather than obsession with power that too often characterizes life today under the banners of social justice or corporate globalization. It is as if a quantum dimension to our lives. In keeping with this,

Jesus called us in personal sacrifice to love our neighbor more than ourself (“greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends”). We fail often too miserably.

But Dostoevsky felt, from the long Lenten period in his own life, that there was resurrection to come in Jesus Christ and the love He inspires, the promise of spring woven into Great Lent.

After the murder of his physician father, he had become a revolutionary in spirit. Caught transmitting inflammatory and prohibited literature, he was sentenced to death for revolution with his literary posse. The firing squad lined up, he and his comrades prepared to die. Then suddenly came a reprieve from Tsar Nicholas I. It turned out that the Tsar had stage-managed the whole event to scare the radical youths out of their wits.

It seemed to work with Dostoevsky. He served out a sentence of several years of forced labor in Siberian exile followed by military conscription. He became a devoted if imperfect Christian, coming to regard revolutionary ideology as a great plague of modern life. His books prophesied vast destructions to come under ideological banners like Communism and Nazism. He found his need to forgive and ask forgiveness as the great doorway to repentance. He felt his youth had been wasted in ideology and activism deluded by utopian ideas. He saw it all as really about the will to power.

Out of his quest for forgiveness, forgiving, and repenting, his novels became a gateway into the human heart that led non-Christian thinkers such as Sigmund Freud and Albert Einstein to praise him as one of the great psychologists of all time. He is considered a brilliant existentialist by many far from the Orthodox Church. But his stories took root in his own struggles with gambling addiction, epilepsy, and various sins, and the loss of his young son Alexei, as well as in his deep faith. After his son’s untimely death, the deeply grieving Dostoevsky went to see Saint Ambrose the Elder at Optina Monastery. From that experience of holiness came his greatest novel, The Brothers Karamazov, whose protagonist was named Alexei after his dead son.

The novel with its message of forgiveness brought many to a deeper sense of Christianity. It helped lead me into Orthodoxy from my own Midwestern family religious backgrounds in old Yankee cults of Christian Science and Unitarian-Universalism, and ultimately into the Orthodox clergy.

The gate to Lent marks the start of an ancient road of pilgrimage, asking forgiveness as a gateway to repentance. King David traveled that lonesome highway. After murdering a man to commit adultery with his wife, the egotistical David was reminded of his sin by the Prophet Nathan. Nathan told him the story of a rich man who stole a poor man’s prized possession, a lamb. David the King, outraged, promised harsh justice against the villain. But who was the evil-doer, he wanted to know? “Thou art the man,” said Nathan. David’s royal Teflon veneer broke. His long road of repentance led to the writing of most of the biblical Psalms, according to tradition, especially Psalm 51 (50 in the Orthodox Bible): “Create in my O God a clean heart, and renew a right spirit within me… The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit, a broken and contrite heart Thou O God will not despise.”

Some years ago, I was struggling in a new career and new marriage, leading me to a new part of the country, my wife expecting a child. But my parents had fallen badly ill one by one. Our plan to move them out to a home in our new locale was for naught.

I had so much to ask them to forgive. When I finally realized that pride itself was the biggest thing I needed to ask forgiveness for, it was too late.

But with each of them on their death bed just a few months apart back in Chicago, I was able to be with them on their final day, holding their hand, praying with each of them separately a famous Orthodox prayer: “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me.”

The asking of forgiveness from them was too late on my sinful part, although I did as we expressed love for each other.

But in the mystery and grace of God’s beyond-time, it is never too late to recognize our own pride and offensiveness, while having the breath to do so and trying to comfort others, however unworthily.

For each Lent is also spring time, a bright sorrow.

-30-

Father Paul “Alf” Siewers is priest at an Appalachian mission parish of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia in central Pennsylvania, where he is also on the faculty of Bucknell University as associate professor of literature. He is a native Chicagoan who grew up in West Rogers Park. His great-great-grandfather was at the convention that nominated Lincoln in 1860 and his grandfather worked a small farm in Edgewater. He is the son of a Chicago Public School principal and schoolteacher, and formerly worked as Urban Affairs Writer for the Chicago Sun-Times.

Father Paul “Alf” Siewers is priest at an Appalachian mission parish of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia in central Pennsylvania, where he is also on the faculty of Bucknell University as associate professor of literature. He is a native Chicagoan who grew up in West Rogers Park. His great-great-grandfather was at the convention that nominated Lincoln in 1860 and his grandfather worked a small farm in Edgewater. He is the son of a Chicago Public School principal and schoolteacher, and formerly worked as Urban Affairs Writer for the Chicago Sun-Times.

Comments 17

Amen John. It is all about love, and forgiveness and Easter Orthodox Easter is very Special and Easter should be special for all Christians. Christ is one in all and for all. Rich or Poor we will all see the Lord someday. Kali Sarakosti John. Forgive and walk away is my Philosophy. Love all as a Christian and take care your Soul.

Amen John. It is all about love, and forgiveness and Easter Orthodox Easter is very Special and Easter should be special for all Christians. Christ is one in all and for all. Rich or Poor we will all see the Lord someday. Kali Sarakosti John. Forgive and walk away is my Philosophy. Love all as a Christian and take care your Soul.

Fascinating career trajectory of this Chicago native. Hope he’ll write more.

This was good. Thank you Father Paul.

Thank you for this insightful, warm-hearted invitation to Lent and Easter. Truly, asking forgiveness is the gateway to repentance . Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me, a sinner.

Perfect and timely

Thank you Father

I am in tears at such poignancy and I hope to take this lesson you have offered to heart. Thank you.

Beautifully said and absolute truth.

It is never to late to ask for forgiveness through Jesus Christ! Thank you Father Paul and Dostoevsky is one of my favorite authors.

Beautiful, Father Paul! I am in awe of your fascinating journey, and hope to read you here again. Lenten and Easter blessings upon you.

Thank you John for posting Father Paul’s writing for your readers.

Eastern Orthodox who follow the Julian calendar, at least for religious days, celebrate Easter following the first full moon after Passover when the crucifixion and resurrection of Christ took place after Christ entered Jerusalem to celebrate Passover.

Thank you for this.

Asking forgiveness while giving it

Most beautiful Father Paul!

Lovely Homily for all faiths! Well done, Father!

Thank you Father Paul. Beautiful Lenten prayer. Thank you

I remember Alf from the Sun-Times. A good, decent and caring man who brought light to the otherwise dark room. Thank you Father Alf for reminding me of the true nature of forgiveness, of which I need plenty.

Amen Father, and thank you Yianni for posting. As Orthodox Christians, we must all remember that without forgiveness, we are doomed to suffer. We are instructed to forgive those who’ve wronged us, and move forward with a clean heart. If we hold resentment and hatred toward those who have transgressed against us, it will surely destroy our souls. I found out early on and saved my soul from eternal darkness – and felt SO much better for it, – that those evil doers no longer had a hold on me! Try it – it works! Kali Anastasi to all my Orthodox brethren.