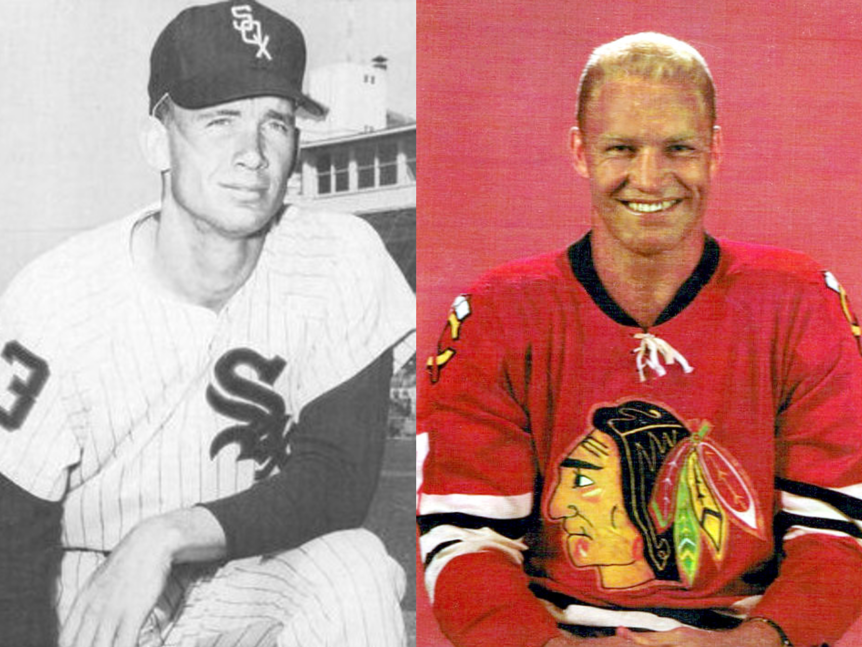

Gary Peters and A Golden Age Pitching Duel in Chicago

by Cory Franklin

February 5, 2023

When Bobby Hull died in January it marked the passing of one of the last great figures of the mini “Golden Age of Chicago Sports”, the period from roughly 1958-1964. During that time, the White Sox wrested the 1959 pennant from the New York Yankees (more on that below), the Bears won the 1963 NFL Championship, Loyola University won the 1963 NCAA Basketball Tournament and the University of Illinois, led by surviving Golden Ager Dick Butkus, won the 1964 Rose Bowl . There was even a week in 1962 when Northwestern was the #1 ranked football team in the country.

In 1961, the tandem of Hull and Stan Mikita helped break the Montreal Canadiens stranglehold on the Stanley Cup. The old Chicago Stadium was a raucous place when Michael Jordan played for the Bulls, but it was never louder than when Bobby Hull started behind his net, skated up the ice and launched a booming slap shot from the blue line at a hapless opposing goalie.

Bobby Hull’s death overshadowed the recent death of another Chicago sports figure of that era, one who might have become a star but for circumstances. Gary Peters, a slick lefthander, came to the White Sox in their pennant-winning season of 1959, but because of the strength of the Sox pitching staff, he did not break into the rotation until 1963. When he did, he was fantastic; as a rookie in 1963 he led the league in ERA, won 19 games, and was voted American League Rookie of the Year. Only a single Cy Young Award was given for both leagues in those days, and had it not been for the preternatural Koufax in the National League, Gary Peters might have been the winner.

Following that, he won 20 games in 1964, led the league in earned run average in 1966, and was a two-time All-Star. Among the best hitting pitchers in baseball, he was Shohei Ohtani before there was Shohei Ohtani. He was so good that he became the Sox’s primary left-handed pinch hitter, a decade before the designated hitter rule. In 2000, Peters was named to the White Sox All-Century Team, one of nine pitchers representing the first 100 years of their existence.

I have a personal connection here – a game I attended against the Yankees with my father on a Saturday afternoon in June 1964 with Peters pitching at Comiskey Park. I forget whether it was for Father’s Day or for my birthday but it remains one of the most memorable baseball games I ever saw. (Though I recall it vividly, I have supplemented some of the details with the New York Times account, which it described the game as a “Rembrandt.”)

The White Sox had been the #1 baseball team in Chicago since the end of the war. Starting in 1951, they drew over one million fans every year but one; the Cubs, by comparison, had drawn one million fans only once in that interval. In 1964, the Sox would outdraw the Cubs by nearly half a million fans. And the highlight of the season was when the Yankees came to town.

Since 1949, the Yankees had won 13 pennants in 15 years and the 1959 Go-Go White Sox were the last team to dethrone them. In those days, a four-game series with the Yanks at Comiskey Park would easily draw more than 100,000 fans, including a Friday night game with a full house. Everyone came to see Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris and the Bronx Bombers. In 1964, the two teams, one pitching laden and the other stocked with sluggers, were fighting for the pennant.

The Yankees were still the class of American League but the cracks in the façade were beginning to show. Koufax and the Dodgers had shut them down in four games in the 1963 World Series, and injuries began taking their toll on Mantle, Maris and several regulars. They were ripe for the picking by the Sox.

The game that afternoon was a dream matchup. Peters’s opponent was the best American League pitcher of his generation: Whitey Ford, aka The Chairman of the Board. Coming into the game, Ford had notched ten straight wins including six shutouts and had not given up a run against the White Sox since August of the preceding year. He had been nearly untouchable.

That day, Peters v. Ford was a masterpiece and more than lived up to its billing with the Yankees winning 1-0 in 11 innings. Both pitchers threw complete games and Peters actually outpitched Ford until the decisive 11th inning. Peters gave up only four hits before that, two of them to Mantle, before surrendering three in the 11th including another key hit by Mantle. Ford was in trouble several times, once with Peters reaching third after a hit. But he escaped several jams and ultimately the Sox were undone by their weak bats (one of the perennial White Sox problems in that era was that Peters was a better hitter than half of the starting line-up.) With the tying run on base in the 11th, Ford retired 40-year old pinch hitter Minnie Minoso to end the game.

The significance of the game was little appreciated at the time but it ultimately took on tremendous importance. At the end of the season, the Yankees won the pennant over the White Sox by a single game.

Peters had two more great seasons but the close loss in the 1964 pennant race took something out of both him and the team. The Sox had two nondescript seasons in 1965 and 1966, but made a final stand in 1967 in a tight four-team pennant race. In the last week of the season they were favored to win the pennant, with their last five games against Kansas City and Washington, the two worst teams in the league. Three wins would probably clinch, but the Sox lost all five and the pennant. The team was broken up, Peters developed arm trouble and was traded after two more lackluster seasons. He was out of baseball less than a decade after his superb rookie season.

The Sox had a brief resurgence in the mid 1970’s with the “South Side Hitmen” but remained in the wilderness until they won the World Series in 2005. More important, after 1967 the Sox surrendered their Chicago baseball primacy to the Cubs, a position they never regained.

But the 1-0 11 inning victory was a pyrrhic victory for the Yankees as well. Times reporter Leonard Koppett wrote, “After the game, the seventh straight the White Sox have lost to the Yankees this year, Sox manager Al Lopez ordered a session of batting practice for almost the entire squad. It may help against other, more mortal pitchers, but not against Ford in his current form.”

Unfortunately, after that game Ford did prove to be mortal. The heavy innings put a stress on his hip and pitching arm. He went six weeks without a victory and, although he rallied at the end of the season and opened the World Series, he was shelled against the redoubtable Bob Gibson and the Cardinals. He did not pitch again in the Series and with everything on the line in the seventh game, Ford, who held and still holds the record for most World Series wins, watched from the bench. Gibson won the Series for the Cardinals by beating Yankee rookie phenom Mel Stottlemyre, who was forced to pitch on short rest.

Following that 1964 World Series loss, the Yankees imploded and suffered their worst decade since before the acquisition of Babe Ruth in 1920. Mickey Mantle, who ten years before had been not only the best player in baseball but one of the greatest players ever, saw his skills deteriorate rapidly, accelerated by injuries and carousing. Before that fateful Sox game in June, Whitey Ford held the Major League record with a .726 winning percentage and over 200 wins, but after that game he won only 27 more and lost an equal number.

There will never be another baseball game like that 1964 Yankee -Sox game. Two aces pitching 11 tense innings with nary a relief pitcher in sight (and no designated runners on second in extra innings.) The game came in under three hours (the average-nine inning major league game today is three hours and three minutes.)

In 1964, there was no free agency so Gary Peters could not play for the team that best suited his skills. There were no pitch counts, video rooms, computers or front-office Ivy League graduates dictating the optimal in-game strategy. And now baseball is unquestionably a “better” game if better means more skilled, athletic players in a highly programmed contest. But that’s like saying today’s cars, with airbags, crumple zones, computerized dashboards and automated features are “better” than the classic cars of the past. Sure, your Toyota may last for 300,000 miles and get great mileage with low emissions – it’s a safe, reliable appliance. But it will never evoke the feelings kindled by the comparatively inefficient 1957 Thunderbird or 1959 Impala.

In that sense, I feel sorry for today’s baseball fans – they will never know the sheer artistry of a young Gary Peters and an old Whitey Ford locked in an extra-inning pitchers’ duel in the middle of a pennant race at Comiskey.

-30-

Cory Franklin, physician and writer is a frequent contributor to johnkassnews.com.

Cory Franklin, physician and writer is a frequent contributor to johnkassnews.com.

He was director of medical intensive care at Cook County Hospital in Chicago for more than 25 years. An editorial ng the pathologists who studied it intently but had no idea what body part it could be. This was before it was known as trolling.)

There is a lesson here. The next time someone tells you, with unmistakable conviction, that he believes in “the science,” gladly offer to discuss science with him over a sandwich. Give him a choice, chorizo or perhaps kosher salami. board contributor to the Chicago Tribune op-ed page, he writes freelance medical and non-medical articles. His work has also appeared in the New York Times, Jerusalem Post, Chicago Sun-Times, New York Post, Guardian, Washington Post and has been excerpted in the New York Review of Books. Cory was also Harrison Ford’s technical adviser and one of the role models for the character Ford played in the 1993 movie, “The Fugitive.” His YouTube podcast “Rememberingthepassed” has received 900,000 hits to date. He published “Chicago Flashbulbs” in 2013, “Cook County ICU: 30 Years of Unforgettable Patients and Odd Cases” in 2015, and most recently coauthored, A Guide to Writing College Admission Essays: Practical Advice for Students and Parents in 2021.

Comments 39

What a joyous history lesson! Thank you Dr. Corey Franklin!

Great column, great memory Dr. Franklin. One more point regarding the 1964 season. Late in the season (August, I believe) the Yankees came back to Chicago for 4 games (Monday thru Thursday).

As a kid I watch every inning of the 3 nite games (Monday thru Wednesday) then trekked down to Comiskey Park (it will ALWAYS be called that by me and nothing else) to attend the 4th, final game, during the day. THE WHITE SOX SWEPT THE YANKEES: 4 STRAIGHT VICTORIES. Only to have the Orioles come in and take 3 of 4 games!!

BTW: before Peters became a pitcher he was a very good 1st baseman in minors.

Tom Rudd, M.S., M.D.

I agree. But as a kid during those times, and a rabid Cubs fan, that regularly took it on the chin from my many Sox fan friends in ’64, ’65, and ’66, I have a small correction to make. It was actually an unexpected Cubs surge in ’67 that more so turn the tide in favor of the Cubs than the Sox collapse. The Cubs were dead last in ’66, and amazingly won 87 games in ’67 and actually were briefly in first place during July. Long suffering Cubs fan were euphoric, and for once I could go toe to toe with Sox fans. It was my favorite baseball year ever, certainly much better than the cataclysm that occurred two years later!

But Dr. Franklin is right on with the idea that the game was MUCH better than. No wretched DH, tons more strategy, starting pitchers that actually pitched the entire game, and players that actually hustled to take an extra base, or stole a base, or hit and run, instead of just sitting back and waiting for a home run. I don’t ever watch a game anymore, just loosely follow the scores and standings. I don’t think I’m alone, given that the World Series now gets about the same TV ratings as Beverly Hillbillies reruns. The players union and owners got what they deserved.

Dr. Franklin,Thanks for the Gary Peters story! He was my boyhood hero (alongside Pete Ward). But I have a medical issue. While reading your piece, I somehow was overcome by the smell of hot dogs, beer, cigar smoke, and Andy the Clown! What is wrong with me?

Go,go Sox,

TEE

I remember those Sox/Yankees games so well. Mantle and Maris were called the M&M boys. I was 14 when this Peters/Ford matchup happened. I also remember the Chicago Fire Commissioner setting off air raid sirens when the Sox won the 59 pennant. During the height of the Cold War and air raid drills in school every Tuesday , setting off the air raid signal for the six did cause some worry for Chicagoans.

Thanks for a great memory of my boyhood hero.

Thank you for the escape, Dr. Franklin. You took me back to some of my greatest childhood memories. I thoroughly enjoyed your story!

Loved him. I was at the Old Chicago Stadium, now that was an incredible stadium. Anyway, I saw him hit his 600th goal. My Son was little when he saw him play at the Stadium, loved hockey. Bobby Hull use to come to Ridgeland Park, in Oak Park and teach the young kids hockey. My Son loved Bobby Hull, his first girl friend was Renee Pilote, her Father was Pierre Pilote. My Son was 11 when we moved out of Oak Park, grew up there and when we moved he was an All State Football Player and a great Hockey Prayer in High School. How America has changed since the 60’s. Obama and his wife do not like America they said so, and he said he would change the face of America and he is doing just that. They want Illegals to Vote for Democrats so they do not have to run for office again, they can keep getting Elected, and Schumer said just that. America is gone the way we knew it, the kids and the American Majority Population has been brainwashed and I feel sorry for them, because their children and grandchildren will be the Minority kids in the Country. I will follow you John, and greatly respect you and I recommend you to all that I know, but I am afraid I will not be sending you comments any more, what is the point no one is listening. I will follow my Lord, and live my life the best way that I know how. Even the Pope and most Christians have given in to that awful Philosophy. Be healthy and safe and speak the truth. God is in charge and sad that people do not know that. Greed is taking over our World.

Helen, I bet you’d be surprised at how many people are listening especially when you mention our Lord and Savior, Jesus. Don’t give up, keep pushing back, the left wants you to quit, don’t give it to them.

Christ’s example is one of empathy, compassion, love and charity, none of these qualities are ever reflected in your comments. Who exactly are you ‘following?’

WARNING:

RigaTony is actually identity thief, Tony Cesare. Kass calls him the “cockroach in a gas station urinal.”

Never reply to him or comment. He will troll you endlessly. He has trolled me.

Here is the proof of how he attempted to steal the identity of the owner of this place from n Wisconsin.

https://www.gardendesignquickstartguide.com/2022/09/come-for-our-durp-burger.html

Actual footage (allegedly..) from the Trailer Park where DuRP lives (allegedly..)! A neighbor perhaps? (Allegedly, right DuRP?? Allegedly??) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aF8_y2Zl9W8

Yep, I figured that out last week.

Check out Harvey Haddix v. Lou Burdette, May 26, 1959.

IMO the greatest game ever pitched – at least in my lifetime – was in 1963: Marichal v Spahn. 16 innings, 1 – 0 Giants … decided by a HR by the GOAT himself, Willie Mays.

It truly was a golden time for Chicago sports. I also don’t think “progress” necessarily is always better, the game of baseball has not changed for the better, and you’ve summarized some of the most glaring reasons why. Money, greed, and shortsightedness is the only reason our Chicago sports treats are not more competitive in the third largest market in the country. Our owners are backwards, greedy, not innovative in the least, and won’t pay for talent.

The players were essentially indentured servants to the clubs they toiled for. Mike Trout did not hold a gun to anyone’s head to sign his 300 million dollar contract. I doubt the Golden Jet, the wife beater, would have played in Chicago as long as he did because someone would have ponied up the cash, as the Winnipeg Jets later did, and the equally disgusting , cheap, greedy Wirtz family would have cheap shotted him out the door. Labor snd ownership could partner together to remedy many of the ills in sports, but greed on both sides gets in the way.

The NBA essentially has a revenue sharing model now with the players. They have a salary cap and a floor, and the players have freedom. The corporatization of sports has killed much of the joy and purity for the game however, and it’s not solely the players’ fault. If you think the Blackhawks or the Bulls would charge any less for tickets if the players played for free, I want to know what you’re smoking. If these bastards that own these teams could hold us by our ankles and shake us till all our money fell out, they would.

Baseball has seen too much expansion, they skimp on scouting, development, the minor leagues. The only reason the Cardinals are decent year in and year out is they still sped a little on player development and don’t just rely on stats and computer models. If MLB jettisoned a half dozen teams, and put that money in to player development, they’d be much better off. Hockey too, there’s too many teams, the talent is diluted.

Wringing out profit has decimated health care, education, manufacturing, everything. Look at Covid 19 and how corrupted the whole thing got due to greed.

Thank you, Mr. Franklin, for the memory of a time when ptofessional baseball meant something – when the players were truly elite athletes because the game required they play both offense, and defense. Time all but stopped during a baseball game, then.

In that era, professional baseball united people from all walks of life – the play-by-play announcers on the radio were better, too.

Great column but it makes me feel old (which I am, lol). Bobby Hull and Gary Peters were two of my boyhood idols along with Jim Landis and Ken Berry. Two others who also recently passed, Joel Horlen, (I saw his no-hitter 9/10/67) and Ray Herbert.

I remember well the twi-night doubleheader that last week of the ‘67 season. We pitched Horlen and Peters against the Athletics that evening. The A’s were lead by interim manager Luke Appling. Speculation was the outcome was never in doubt for the Pale Hose. KC had brought up a few of their younger ball players some of which would be vital cogs in their World Series championship teams in the early ‘70’s. Well, we lost both games and came home only to lose three games to the Senators. What could have been ?

Thanks for the memories.

Great column. Thoroughly enjoyed it. If you are a football fan, too, it would be great to read a column about those 1963 Champion Chicago Bears.

That was a great piece. I grew up in Crown Point Indiana, and my Dad & brother were avid Sox fans. I rooted for the Yankees. I have been to many games over the years in Chicago in 1960s & 1970s, St. Louis in the 1980s when I lived there, and now in Atlanta where I’ve lived since 1990. I root for the Braves these days and in fact have season tickets having gone to about 4o games last year now that I’ve retired. I remember vividly that 1964 game where the Yankees won 1-0 since that was the first MLB game I ever attended – we sat in the last rows of the upper deck behind home plate. This was a great column and I thank you for posting it!

Awesome column and the picture you paint makes me feel like I was there. You also illustrate how bastardized baseball (and sport in general) has become and how clowns like Bud Selig and especially Rob Manfred destroyed a great game with the silly rule changes and their desire to leave a legacy. Thank you Dr Franklin for taking us back to a time when life, not just sport, was simpler and certainly not polarizing.

Great article, brings back great memories of old Comisky Park

One of the best group of starting pitchers: Gary Peters. Joel Horlen, Juan Pizzaro, & Hoyt Wilhelm. The following year they added Tommy John and sent Wilhelm to relieve. The old Go-Go White Sox.

Part of what makes these memories stand out for us now is their uniqueness. And one of the key variables making them unique is subsequent change. Had the baseball rules not changed, maybe there would have been other such games. Who knows?

I’ve wondered what special memories my kids will have when the reach the I-remember-when stage of later life. I think evolving change will help shape and preserve things happening now to be their nostalgia.

Great memory to have! It reminds me of the classic pitching duel between a young Juan Marichal and Warren Spahn – 16 innings by each guy (16!!!) with Marichal winning 1-0 on a Willie Mays home run. And, although I can’t recall the exact game, Nolan Ryan threw over 200 pitches in a complete game victory. Fergie Jenkins had 31 complete games pitched in one of his 6-consecutive 20 game victory seasons. And then, somewhere along the way, a “pitch count” was force-fed on both the game and the fans. In my opinion both are worse off for it.

“..they will never know the sheer artistry of a young Gary Peters and an old Whitey Ford locked in an extra-inning pitchers’ duel..” Well no, but I’ve seen Dylan Cease come within an out of a no hitter against the Twins last year. I’ve watched the 2005 pitching staff, the most dominate in playoff history. I watched Chris Sale as a rookie, it looked like his arm would snap throwing sliders at 97MPH. “Black Jack” McDowell was the most underrated pitcher of his era, and a great guitar player to boot. What about Mark Buerle? Ring a bell? Threw a perfect game, which is like, really hard to do. Hope springs eternal every season’s beginning and myself (and son..) are looking forward to this one, same as we always have. I feel sorry for those stuck in time, looking back at some imagined ‘golden age’ while bemoaning everything around them as somehow inferior. The game is still great, always will be. Sounds like someone needs to pick a warm day this Spring and buy a bleacher seat and a cold Miller Light, just might make you feel young again..

WARNING:

RigaTony is actually identity thief, Tony Cesare. Kass calls him the “cockroach in a gas station urinal.”

Never reply to him or comment. He will troll you endlessly. He has trolled me.

Here is the proof of how he attempted to steal the identity of the owner of this place from n Wisconsin.

https://www.gardendesignquickstartguide.com/2022/09/come-for-our-durp-burger.html

We called the real owner of Tony’s Tao in Mineral Point WI. And we spoke to his wife and a few staff. They have never heard of Tony Cesare. Never!

I attended a similar Sox-Yankees game eight years earlier on a night in June 1956, with many similarities to this 1964 game but with a better ending. The game was sold out and we had two tickets for the four of us, so my Dad scored two more in a bar and we sat on the aisle steps behind home plate to watch Dick Donovan, who pitched 11 innings, doubled and scored. Minnie Minoso, who was not in the lineup because of a broken toe, pinch hit in the 11th with a double off the top of the right-center field wall. After hobbling into second, Billy Pierce came in to pinch run, and scored to tie the game. The other hero was Sammy Esposito, who pinch hit for Luis Aparicio, and had 2 RBIs including the game-winner in the 12th. Sox 5 — Yankees 4.

I could read stories all day long about the great sports rivalries from days gone by. I can hardly get through a baseball game now on TV with all the meaningless stats, metrics, pitch counts etc. and don’t get me started on the players stepping out of the batting box after every pitch to adjust their batting gloves. Mark Buehrle was my hero, his pitch was coming no matter if you were in the box or not, 15-16 seconds between pitches. His fastest game was 1 hr.39 minutes on April 16, 2005

From Five Thirty Eight (04-28-14)Buehrle might be even faster if he didn’t have to wait for stalling batters. “It’s annoying,” Buehrle told the Boston Globe last year. “Guys don’t even swing the bat, take a pitch, and then they get out and adjust their batting gloves. Some of it might be just habit or routine or superstition that they do it, but you didn’t even swing the bat — why do you have to tighten your batting gloves?”

As I said, my hero

Gary Peters was my favorite Sox player until Dick Allen came along

What a great column. It brought back memories of my first MLB game attended in person. August 29, 1957 as a 7 year old, Sox lost to the Yankees in 11 innings, Ford beat Dick Donovan who pitched all 11 innings. Sure was a different time for pitchers.

Great column with great memories! Being born in Oak Park in ‘60, I was a bit young in ‘64, but remember vividly the fold-out full-size team photo of the 1959 Go-Go White Sox in my grandfather’s basement in Maywood. I think it was from the Chicago American, but not sure…of course I also have vivid memories of the early Playboy centerfolds that my grandpa had lacquered into the bartop he had hand-built in that same basement, which provided education of a totally different type!

Without writers like Kass and his esteemed clansmen (and women) to help blast the crust off old cranial crevasses, I would never get the opportunity to relive my childhood in the greatest city in the world. Thanks again and keep them coming!

I just love these stories of the good old days of baseball, and I don’t think for a second that baseball is “better” now. It reminds of the 1963 game between a young Juan Marichal and an old Warren Spahn that Willie Mays won in the 16th inning with a home run. 1-0, complete games by both pitchers. Marichal threw 227 pitches; Spahn threw 201. Today, a pitcher will almost certainly be removed before he reaches 100 pitches even if he has a no-hitter going.

Here’s the box score from that game on June 20, 1964 … and just about anything else you might want to know: https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/CHA/CHA196406200.shtml

Interesting points to note:

• Mantle had 3 of the Yankees’ 7 hits. He was hitting .331 at the end of the day

• The only extra base hits were 2 Yankee doubles by Mantle and Phil Linz, and a Sox double by Dave Nicholson

• Ford’s win ran his W-L record to 10-1 with a 1.47 ERA. He would finish the season at 17-6 with a 2.13 ERA

• Peters’ loss dropped his W-L to 7-2 with a 2.96 ERA. He would finish the season at 20-8 to lead the league in wins and post an ERA of 2.50

• Al Weis had two of the Sox’ 6 hits. Peters had one of the hits and was hitting .222 at game-end

• Time of the game: 2:56 … for an 11-inning game

• Attendance for the afternoon contest was 22,453

• The ’64 Sox opened the season with 3 losses. On Sept 19, the Sox were 2 games out with 11 left to play. They closed out with 10 wins in their last 11 games but still finished 1 back of the Yankees who went 23-8 from Sept 1 on through season end (including a 14-1 streak starting in mid September

Peters was my favorite Sox pitcher from those days. My all-time favorite Sox player is Moose Skowron, whom the Sox acquired from Washington about 3 weeks after this game.

Pete Ward was my all-time favorite White Sox player.

He came to the Sox in ’63 along with Hoyt Wilhelm, Ron Hansen and Dave Nicholson in a trade with the Orioles.

My Mom took me to my first MLB game on May 23, 1964 and what a glorious sight it was walking up the ramp behind home plate and seeing that Comiskey Park scoreboard in person for the first time.

We walked to our seats in right-center field and Mom asked why I liked Pete Ward so much. Moments later, he landed a grand slam home run ball 3 seats next to us. And the scoreboard exploded.

“That’s why, Mom!”

Pete Ward died March 16, 2022.

Here’s another way the game has changed since Peters’ time. Gary Peters was being interviewed once after a game and the interviewer asked him what he planned to do in the off season. He replied that he was working on obtaining his teaching degree so he would have something to fall back on after his baseball career. He wouldn’t have to worry about that now – he would be a multi millionaire and could spend his retirement playing golf or doing anything else he wanted to do.

Great story and an exciting read!

And it is wonderful to read all of the memories in the comments, too!

Thanks for the memories, Dr. Franklin.

And don’t forget those great college basketball doubleheaders at the old stadium. Some of the best teams and great players were featured. Marquette, Bradley, and many more. Back when the Missouri Valley Conference was one of the best in America. O