America Needs Virgil’s Aeneid

By Pat Hickey

November 29, 2024

Of arms and the man I sing, who, forced by fate

And haughty Juno’s unrelenting hate,

Expelled and exiled, left the Trojan shore.

Long labors, both by sea and land, he bore;

And in the doubtful war, before he won

The Latin realm and built the destined town,

His banished gods restored to rights divine,

And settled sure succession in his line;

From whence the race of Alban fathers come,

And the long glories of majestic Rome.

The Aeneid, Book One by Publius Virgilius Maro

America is in bad shape. Its soul is weak. Men will text while women are being assaulted. When a man steps in to help the innocent our moral laws drag him to jail and before an un-souled judge.

Like our bodies, our souls need good nourishing and healthy additives. We are bloated with empty, loveless and fatuous nonsense. This Thanksgiving and Christmas seasons I will try and count all of my blessings: American birth, Catholic up-bringing, strong working-class values and ethics and powerful sense of obligation to the past. Being centered requires understanding and reconciliation of the events, people, places and decisions that brought me to where I stand today.

I was blessed to have been fed on a soul-growing diet of thoughts and deeds that linked up with universal and eternal truths. My grammar school education was a standard Catholic working-class experience that was superior to the public education hands down. The Religious Sisters of Mercy were not of the Singing Nun variety and most seemed to have come from County Galway and seemed to detest males with a vigor only matched by their scorn of my Italian brothers and sisters. That said they did a thorough job of teaching discipline, the Catholic catechism, history, arithmetic and respect for the classics in literature. I learned the pronunciation of Latin as an altar boy and more so in the choir.

My first three years of high school were spent in Holland, Michigan at St. Augustine Minor Seminary. There, Father Henry Baines Maibusch, O.S.A. immersed me in Latin grammar and literature. What a magnificent teacher! Old ‘Busch lived the language and his enthusiasm for its majesty and sweep was boundless. We lived the Gallic wars and Caesar’s struggles with snows in the Alps and against the Celtic tribes from Cisalpine Gaul to Britain. Cicero remains matchless for rhetorical and moral force, while Suetonius, Tacitus and Pliny brought the Republic and the Empire to life, We said compline and serotina in Latin and English after dinner and before studies. I received a superior education with the Augustinians. I had no vocation and elected to leave.

I returned to Chicago and elected to finish high school at my parish secondary school, Little Flower. Little Flower High School was co-educational. Leo, St. Rita, Mount Carmel , Mendel, and Brother Rice? Non est pulchra mulier!

The order of nuns running the high school was the Sisters of St. Joseph and compared to my eight years of experience with RSMs the change was magical. The sisters were brilliant scholars and witty instructors. It was like going from a gulag to a hall of learning on the south side. The study of high school Latin generally ran like this: Freshman Year Grammar and passages from Pliny; Sophomore year Caesar’s Gallic Wars; Junior studies in Cicero’s Orations and letters to Atticus and senior year Virgil’s Aeneid with time for the Augustan poets Horace and Juvenal. I was looking forward to this unit but was sad not to have Father Maibusch to direct my work. I was lucky because I got the “The Sarge!”

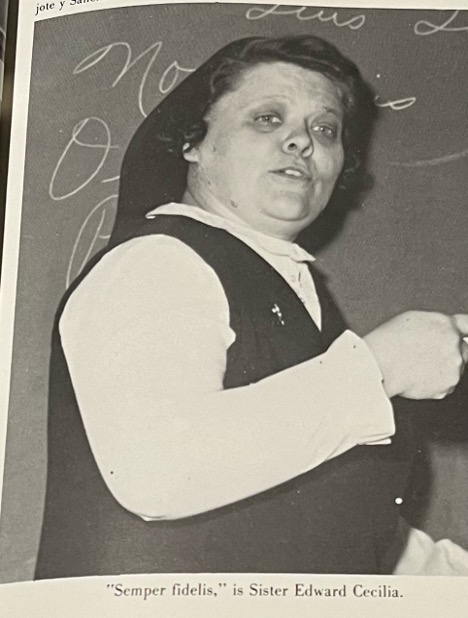

I translated Virgil thanks to this wonderful woman, the Sarge!

Sister Edward Cecilia, SSJ was a formidable scholar and woman of great wit. Virgil was her specialty and like the tragic Dido of that epic poem had deep and abiding love for Aeneas. Sister Edward Cecilia was delighted to have me help bring my fellow Latin students up to scratch in matters of grammar and vocabulary. She said, ” It’s to have someone to talk a Latin with who was not afraid of the power it brings to our lives.” I was deeply aware of that.

We worked out long passages of The Aeneid.

The Aeneid is the Roman national epic consisting of twelve books in dactylic hexameter. The first six books deal with Aeneas’s struggles escaping from the fall of Troy on the Turkish Bosphorus and being buffeted around the Mediterranean by jealous gods and the arrival of these refugees in Carthage, a city founded by the beautiful and brilliant Queen Dido, who herself had fled the angry gods from Tire in modern Lebanon to found a growing and powerful empire on the north African coast. Aeneas and Dido are equally matched in ability, Dido lacks the stoicism of her lover. It is that quality which will mark character of the Roman people, at their best.

The last six books deal with Aeneas and his people landing in Italy and establishing their home among people of Latium. They are not welcomed and must fight mightily to take their place and build the Empire of Augustus, who is the real subject of the poem’s attention. His Julio-Claudian Pax Romana is what the poem is all about. Poets like Virgil, Horace, Shakespeare and even the tiresome Amanda Gorman spend many hours kissing up to the powerful. Shakespeare changed the character of Banquo in MacBeth, from the murder accomplice for in Hollingshead’s Chronicles into a virtue – signaling murder victim MacBeth’s greed for power, in order to flatter the Stuart King James, I, who may have been a blood relative of England’s post-Tudor monarch. Likewise, Virgil stretched the imagination in The Aeneid in order to link the pious Aeneas to the cold-blooded Augustus.

In doing so, as does every great poet, Virgil adjusts a tension between pietas and furor. Piety originally meant one’s sense of obligation to his family, nation and personal honor. Furor is a rage against assaults on dignity, honor and patriotism. I grew up in a union household. My father raged against scabs, people who would take another man’s rightful job and wages, and captains of industry and their agents who would lock-out real workers and hire scabs at much lower wages.

Likewise, this morality would extend to boycotting anti-labor news outlets, entertainment venues and even barber shops. To this day, I can say that I have never crossed a picket line, made purchases at big box retail outlets or vote for scab happy politicians. The Aeneas reinforced my personal morals. Aeneas broke Dido’s heart long before that noble woman put a dagger to her breast. The widower Aeneas fell in love with Dido, but he loved his obligation to his people’s destiny in Italia and forsook the love of the Queen of Carthage. Aeneas seems a heartless cad, but the poem recalls his return to Troy after carrying his aged father, Anchises to safety only to encounter the ghost of his recently murdered wife. Aeneas took his father and son to safety, but lost his dear wife. He would lose Dido, in order to take all of his people to make their destiny in Italy. The good man suffers.

The greatest poet of the last century and this one, Seamus Heaney wrote a translation of Book VI of The Aeneid. This Book details Aeneas’s journey into hell, in order to speak with the spirit of his father. In a masterful review of Heaney’s epic challenge balance the tension between the rhythms of two languages and kinetic energy of facing the dead and returning do the work expected of pious man Lorna Lee writes:

“The reunion between father and son is brief. Soon Anchises begins to direct Aeneas on what is to be the future glory of the Roman race. Heaney describes this part of the poem, in his opening notes, as ‘something of a test for reader and translator alike’; admitting that at this point ‘the translator is likely to have moved from inspiration to grim determination,’ as he trudges through the succession of ‘future Roman generals and imperial heroes’, alongside the ‘allusions to variously famous or obscure historical victories and defeats.’ But though his heart is elsewhere Seamus Heaney navigates the sprawling landscape of Rome’s future history with the same enthralling lyricism as he does the rest of the text. He parallels the tragic beauty of Virgil’s description of Augustus’ nephew and prospective heir, Marcellus, who is arrayed in ‘glittering arms’ (1171), his brow wreathed with ‘dolorous shadow’ (1177) and he captures the slow march of the Latin when Anchises bewails his untimely death: ‘Do not, O my son, | Seek foreknowledge of the heavy sorrow | Your people will endure’ (1179-81), together with the raw emotion sown into the line: ‘O son of pity! Alas that you cannot strike | Fate’s cruel fetters off! For you are to be Marcellus…’ (1197-98) – which, according to Aelius Donatus’ fourth century CE ‘Life of Virgil’, caused Marcellus’ mother Octavia to faint upon hearing it for the first time. “ (emphasis my own)

The more we revere the past, the real past and not some historical legerdemain like 1619 project, or Howard Zinn’s Marxist propaganda as fact, the more we center ourselves and brace for the shocks that life sends rushing our way.

Virgil with the help of Sister Edward Cecilia and Father Henry Maibusch armed this very flawed man.

Let us all count our blessings and honor the past.

-30-

Born November 8, 1952 in Englewood Hospital, Chicago Illinois, Pat Hickey attended Chicago Catholic grammar and high schools, received a Bachelor of Arts in English Literature from Loyola University in 1974, began teaching English and coaching sports at Bishop McNamara High School in Kankakee, IL in 1975, married Mary Cleary in 1983, received a Master of Arts in English Literature from Loyola in 1987, taught at La Lumiere School in Indiana from 1988-1994, took a position as Director of Development with Bishop Noll

Born November 8, 1952 in Englewood Hospital, Chicago Illinois, Pat Hickey attended Chicago Catholic grammar and high schools, received a Bachelor of Arts in English Literature from Loyola University in 1974, began teaching English and coaching sports at Bishop McNamara High School in Kankakee, IL in 1975, married Mary Cleary in 1983, received a Master of Arts in English Literature from Loyola in 1987, taught at La Lumiere School in Indiana from 1988-1994, took a position as Director of Development with Bishop Noll

Institute in Hammond, IN and then Leo High School in Chicago in 1996. His wife Mary died in 1998 and Hickey returned with his three children to Chicago’s south side. From 1998 until 2019, it became obvious that Illinois and Chicago turned like Stilton cheese on a humid countertop. In that time, he wrote a couple of books and many columns for Irish American News. When the kids became independent and vital adults, he moved to Michigan City, Indiana, Hickey substitute teaches K-12 for Westville, Indiana schools and works as a tour guide/deckhand on the Emita II tour boat. He walks to the Michigan City Lighthouse every chance he gets.

Comments 21

Sir,you are a wealthy man to have had these great educators in your life.

Thank you,

Pat,

I enjoyed your column immensely. It brought back some uncomfortable memories though. As an ardent student of Latin, as taught by Mr. Brow in freshman year and Mrs. Delaney in sophomore year, I was thunderstruck when I found out that ours would be the last class of Latin offered at T.F. North! I felt a sense of betrayal that ran so deeply, that my next year at school became a Lost Year of drinking and cavorting in general. Barely able to graduate, I joined the Navy where I really became A Problem. I trace it all to not learning Vergil’s Aeneid. A text that I had been looking forward to with an insatiable desire. A desire, as yet, unfulfilled…

‘For how can Man die better,

Than facing fearful odds,

For the ashes of his Fathers,

And the Temples of his gods!’

You stood guard over our Republic, like Horatius at the Mulivian Bridge! Thank you, for your service, Kevin!

My bad. Horatius stood off the Etruscans at the bridge. The Milvian Bridge was Constantine’s victory for the faith. Still in a turkey induced fog this fine day.

masterful column. politics can’t fix this. it will take national courage, discipline and willpower. Maybe VDH can bring back the classics?

Hickey really nails it. We have the choice to believe magnificent scholarship from Mr. Hickey or the communist garbage from hacks like Howard Zinn. Much too frequently these days, we opt for the latter. Sad.

I sure am jealous of your classical education. I am trying to learn Ancient Greek from online courses and textbooks. Such treasure in Latin and Greek literature.

Pat,

After one boring, painful year of Spanish class I switched to Latin because the teacher seemed like a frustrated stand up comic. The result was life altering. Wonderful, entertaining journey with three gifted educators. We need to bring back the study of classic languages.

The late Joseph Sobran put it better than anyone: “In the last 100 years we have gone from teaching Latin and Greek in high school to teaching remedial English in college!”

Yes Terry. he was correct.

What a wonderful column! Thank you!

Stunningly beautifully written.

Thank you.

Pat

Your column brought back wonderful memories of my high school years at St Ignatius in the 1950’s.

I was in the classical honors course four years of Latin and two years of Greek. Quite amazing for a kid from Bridgeport.

Changed my whole outlook on life for which I have always been grateful.

Great commentary Mr Hickey. I recall amo amas amat from my first year at Q, we didn’t get to read Cicero by second year as the school split and south siders moved to 79th & Western, (now St Rita of Cascia) and then I discovered those of the female persuasion and moved on to Rice. Perhaps this year Veni vidi vice, would be a good way to remember the election cycle and use those years of Latin! Latin was a tough language but the basis for Spanish Italian and French so a useful tool moving forward. BTW perhaps you crossed paths with my ex who was on the Loyola faculty during your sojourns there?

Pat, Yianni,

It’s so sad that no Chicago public school students will ever be exposed to, or enlightened by Virgil’s Aeneid, as you were. A real tragedy. Thankyou for your grasp of our Greek mythology and history.

Latinitas in HS non offerebatur quare non potui studere donec collegium. Tamen et utilem et iucundum et adhuc facio. Sed in iis HHS fuistis! Nihil ex T. Livio???

By the way Professor VDH DID bring back the classics at his university, better than 40 years ago.

Reminds me of Freshman Latin w/ Bro. Cerasoli (aka: Bro. “Sort – of – Smelly”) in 1959 at Bro. Rice. Outer lips encrusted w/ what appeared to be that morning’s repast. Would hold my breath as he talked walking the aisles. Second year was better and could actually read some Latin under a lay teacher. Guess it helped in med school somehow but never appreciated it.

My wife, Jill, enjoyed Latin w/ Sr. Vivian at St. Scholastica’s in the early ’60s but never quite saw the “character building” component.

Damn, Pat. The St. George Christian Brothers didn’t have your magic.

I’m humbled by a true scholar.

Great read. I too attended St. Augustine Seminary but only until the middle of my sophomore year. Father Maibusch was the most disciplined and proper man that I ever knew. My early years were spent in Englewood at 76th and Morgan but I was born at St. Bernard Hospital in 1958.