Veterans Day and “Matterhorn: A Novel of the Vietnam War”

By Michael Ledwith

November 11, 2022

Vietnam was my generation’s war. If fate had bent slightly this way or that I’d have done a year and returned home or not. But it bent toward not having to go and spending four months at Ft. Benning doing Infantry Officers Basic Course and out.

Matterhorn is one of the best books about war ever written.

I was thinking about Karl Marlantes and Lieutenant Mellas this morning as I read this tweet from a combat Marine about the disastrous pull out from Afghanistan:

“The Taliban, true to its words, broke my body; the United States Government, with lies and a smile, broke my heart.”

There it is: Vietnam.

“Semper Fi, brothers,” Mellas whispered to himself, understanding for the first time what the word ‘always’ required if you meant what you said.”

Mellas then tells of how he and his Ivy League classmates joked about the warrior mentality and ‘silly codes of conduct.’ He thinks to himself that his college friends, “protected by their class and sex would never know otherwise.”

“Now, seeing Marines run across the landing zone, Mellas knew he could never join that cynical laughter again. Something had changed. People he loved were going to die to give meaning and life to what he’d always thought of as meaningless words in a dead language.”

Semper Fidelis.

These words come from an extraordinary book, Matterhorn: A Novel of the Vietnam War. It’s the best novel I have ever read about Vietnam, which is saying something as I loved “Going After Cacciato” and “The Things They Carried.”

“Matterhorn” is one of the best books I have ever read.

I quote Mellas because I have found it so difficult over the years to explain anything about the military to those who have never experienced it. By ‘it’ I don’t mean combat or war, but the common daily self-sacrifice, sharing, loyalty, and faithfulness between the members of any military unit. The ‘knowing’ that the man or woman next to you will do their job or die trying. Every one of them, every time.

When I think of bravery, I think about that snippet of video from inside one of the towers on 9/11: office workers, crowding the stairwells, trying to escape the smoke and flames and confusion of such an unimaginable occurrence. Moving, in an orderly fashion, down, down, floor after floor, clinging to the wall, calm in the face of death. Then on the video you see firemen, with their archaic helmets and red Irish faces, resolutely moving against the flow, heading up into the maelstrom, toward the danger. Their faces set, their eyes open to peril, their duty clear. Firemen. Semper Fi.

From now on when I think of bravery, I will also think of Mellas’ platoon running to their helicopters knowing, like the firemen, they are moving toward the danger not away from it, honor bound, always faithful, to their duty.

Matterhorn takes place after everyone knows that Vietnam is a complete disaster. Peace talks have already begun. Electoral politics infect all combat decisions. A company of Marines sits on top of a mountain near Laos hacking out a firebase to control what the North Vietnamese may or may not do as the war drags on. Mellas, the new platoon leader, fresh from college, is a kid among other kids. He has life and death authority over thirty men. Young men of every race, from small towns and urban ghettos, most just out of high school, but, as they endure under the worst possible conditions, they are all Marines.

Unlike most Vietnam war novels Matterhorn spends little time back in the States sketching back stories to its characters or contrasting combat with romantic interludes of R&R in Hawaii or Bangkok. It spends its time immersing the reader in the day to day of a rifle company in the jungle. We live and die for a month with Bravo Company, First Battalion, Twenty Fourth Regiment, Fifth Marine Division.

After a few pages there is little distance between writer, reader, and these Marines. I texted someone as I read the book on my deck that I had goose bumps, and my heart was pounding after a description of a fire fight. I became lost in the story. I felt the oppressiveness of the jungle, the abysmal conditions of living in a monsoon with little food, less ammunition and constant fear. I trudged along with Bravo carrying wounded who couldn’t be medevaced because of fog, radios crackling with absurd orders from colonels sitting in air-conditioned bunkers miles away. Regimental officers looking at maps with gradient lines, and not seeing bamboo, elephant grass, steep cliffs and mines, making snap decisions that will cost lives. More worried about command time and promotions than the men in the jungle. Issuing orders that will kill 18-year-olds and having drinks afterwards.

As the men in this book say again and again: “There it is.”

Matterhorn is unflinching in its honest portrayal of America’s second original sin: Vietnam. Nothing in American politics has been the same since. No one has believed what the government has told them about anything since. Fifty-five thousand dead American soldiers. A million Vietnamese. Hills like Matterhorn taken at the cost of dead young Marines, abandoned immediately, only to be taken by young Marines a week later in some circle of hell that Dante missed.

There it is.

Karl Marlantes, a highly decorated veteran of Vietnam, worked on this book for thirty years. I saw an interview with him on YouTube last night. He talked about how, after he came home from the war, he was sitting on a front porch with a pretty girl that he liked. At some point he told her that he had been in Vietnam and that he was a Marine. She was appalled. Marines were the worst of the worst she said and stalked off. Such were the times. He wanted to go after her, to explain the reality of his experience, of the brave men he led, their valor in the face of death and stupidity.

It took him thirty years to write the story he wanted to tell her. Matterhorn is a great American novel. Marlantes had to write it.

You owe it to him and the thousands of other seventy-year-olds who were there, to read it.

You owe it to the thousands of thirty somethings who are back from Iraq and Afghanistan working as cops and fireman, in your office, teaching your kids, to read it.

Perhaps then, you will understand what ‘always’

requires.

Semper Fi.

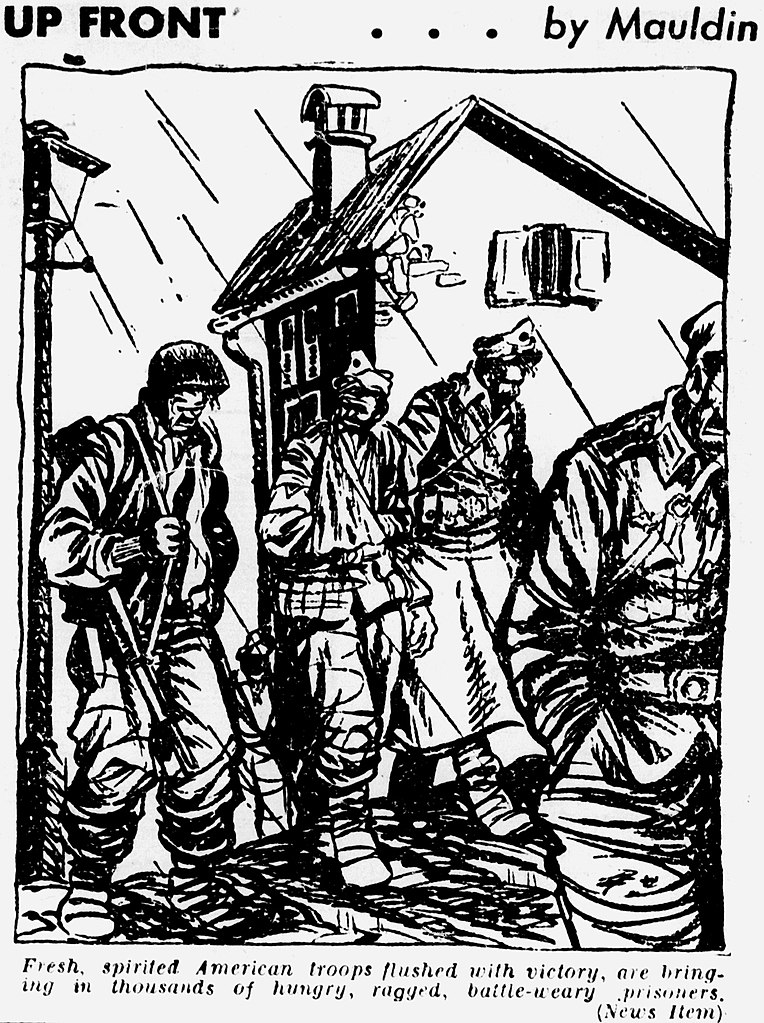

“Fresh, spirited American troops” from the series Upfront with Mauldin in “Stars and Stripes” October 11, 1944

-30-

Frequent contributor Michael Ledwith is a former bag boy at Winn-Dixie. He worked on the Apollo Program one summer in high school. U.S. Army officer. Ran with the bulls in Pamplona. Surfer. Rock and roll radio in Chicago. Shareholder, Christopher’s American Grill, London. Father. Movie lover—favorite lines: “I say he never loved the emperor. Never!” and “You know, I’d almost forgotten what your eyes looked like. Still the same. Pissholes in the snow.”

Frequent contributor Michael Ledwith is a former bag boy at Winn-Dixie. He worked on the Apollo Program one summer in high school. U.S. Army officer. Ran with the bulls in Pamplona. Surfer. Rock and roll radio in Chicago. Shareholder, Christopher’s American Grill, London. Father. Movie lover—favorite lines: “I say he never loved the emperor. Never!” and “You know, I’d almost forgotten what your eyes looked like. Still the same. Pissholes in the snow.”